The Slave Name of Muhammad Ali

(and Islam's Forgotten Slave Trade)

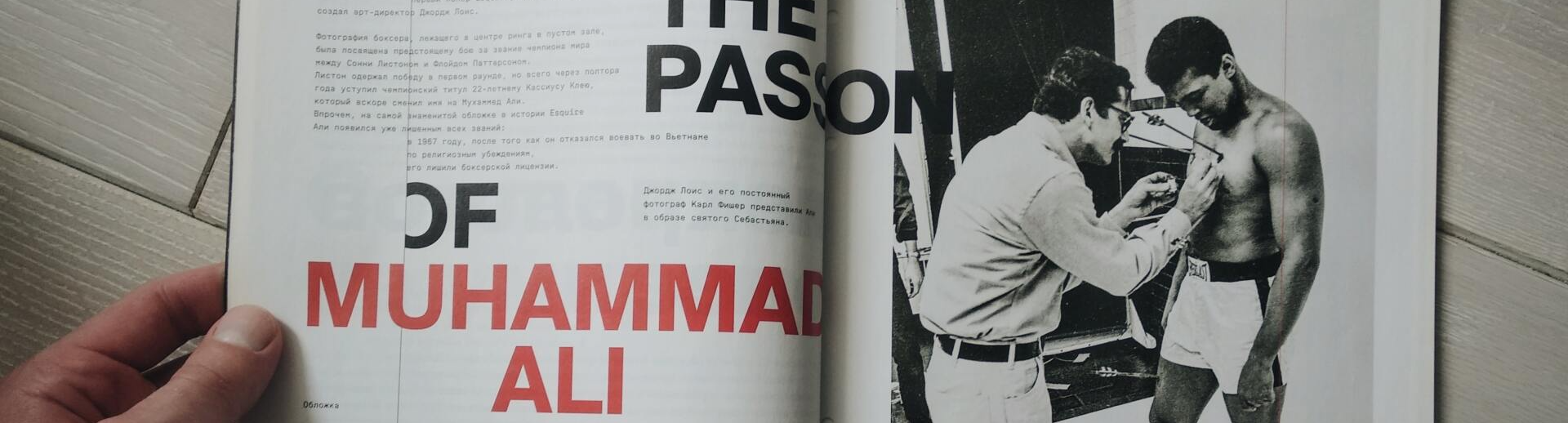

According to many, he was the best boxer the world has ever seen. In 1964 Muhammad Ali surprised everyone by defeating Sonny Liston. He became the ideal champion with stunning technique, brilliant tactics and powerful charisma. Besides an exceptional athlete he was also a human rights activist who spoke out against racism and the draft for the Vietnam war. Less known is the fact that he became captivated by The Nation of Islam, a separatist group of African American Muslims that is ideologically far removed from orthodox Islam.

In the early sixties the group made contact with the rising star that was Cassius Marcellus Clay. The young boxer was told that his ancestors were Muslims and that a new Islamic name would do justice to that heritage. After obtaining his world title, Clay was quick to change his name to Muhammad Ali. This wasn’t the only thing the Nation of Islam conveyed to him. There was also the idea that white people are devils by nature and are for this reason denied entry into the city of Mecca. The movement also believes in the twentieth century redeemer, or Mahdi, called Wallace Fard Muhammad. [1]

Later in his life Muhammad Ali would convert again, this time to Sunnism, Islam’s largest denomination. In doing so he distanced himself from much of the errancy within the Nation of Islam. But his Islamic name remained and, needless to say, was fully accepted by the entire Muslim community. It is likely that it never occurred to him that his new name may also have been the result of deception. A closer look into what we consider a hidden tragedy seems more than fair. For this purpose, three topics will be discussed: First Islamic slavery followed by Ali’s new and old name.

I

Islamic Slavery

During interviews Ali explained his name change by stating that he wanted to be freed from what he called his slave name. [2] After all, Clay was the last name of white plantation owners who held one of his ancestors as a slave. Ali would say things like “we want to be called after the names of our people,“ making the influence of the Nation of Islam quite noticeable. At this point he seemed to believe that his ancestors were originally Muslims, hence the name change. Though the odds are relatively small, it cannot be ruled out that this was true for his more recent ancestors during the moment of their abduction from the African continent.

In the case of his original ancestors this is unlikely, since Islam did not form in Africa but was later imported, often through conquest and its consequence of slavery. The first leg of irony then is the fact that Muslims, like European Christians, have enslaved his African ancestors on a massive scale. Muslims, unlike Christians, began to practice slavery during the very first years of their religion, under the guidance of their prophet.

The slave export

While slavery existed among Africans before, Islamic slavery emerged from the seventh century onwards when Muslim armies conquered large parts of North Africa. The result of these “holy wars” and the establishment of Islamic states was the institutionalization of slavery, with the African “heathen” as its main victim.[3] From then on, in the 700 years before the Atlantic slave trade appeared on the African stage, Islam was virtually the only external influence on the political economy of Africa.[4]

For centuries the northern Islamic states took slaves from the African peoples who lived to their south, mainly East and Central Africa. This slavery was undeniably inspired by Islamic practice, says historian Paul Lovejoy.[5] Most orientalists and Islamic scholars would agree, seeing that this form of slavery goes back to the founding years of the religion. The Islamic system of slavery did not begin to die down until mid-nineteenth century, mostly due to European pressure, then taking more than a hundred years before becoming more or less eradicated.

Indelible theology

After all, Islam’s founding father had owned slaves throughout his ministry as did all his successors. And despite Muhammad’s prescription of freeing slaves for specific reasons, nothing in his instructions indicate that he favored the abolition of slavery, whether gradually or abrupt, says Murray Gordon, writer of Slavery in the Arab World.[6] The Islamic scriptures nowhere mention an overall condemnation of people who kidnap others and force them into slavery, contrary to the New Testament.[7] This led to thirteen centuries of slavery as an indelible part of the social system in the Islamic world. That slavery held out for so long has much to do with the fact that it is deeply rooted in Islamic law.[8] Many orientalists share this conclusion.[9]

The main routes

Africa became an important source of slaves, mostly due to the religious demand that new slaves be non-Muslims, even though states at times deviated from this theoretical approach.[10] The latter was to the dismay of many religious scholars, such as the famous Ahmad Baba, who time and again pointed out that Sharia exclusively permits the enslavement of non-Muslims.[11] Apart from the dividing line between slave and freeman on the basis of religion, there was also a clear preference for women and children. Both these characteristics were not shared by the Trans-Atlantic trade.[12]

The Islamic trading routes are mostly known by the names of three major trails: the Trans-Saharan, Red Sea, and East-Africa routes. These served markets within Africa as well as in the Middle East, West-Asia and India.

Here some may point out that the Islamization of more than half of the African continent was not the result of conquest and enslavement alone. Parts of West, Central and East Africa were indeed reached by Islam in various forms such as trading relations and the conversion of several local kings. But then again, this is an additional reason why Islamic slavery came to those areas, south of the northern Islamic states.[13] Muhammad Ali’s name change simply brought him to a different people that have forced Africans into slavery by the millions and were, to an extent, still doing it in his day and age.

Treatment of slaves

For many years, in East and West, there has also existed a misconception surrounding the treatment of slaves in the Middle East and other Islamic areas. It was said that they all shared a fate several times better than the slaves in the Americas, even to the paradoxal point of having an “intimate relationship” with their masters. This myth was debunked, for the most part, by more modern historians like Bernard Lewis in his book Race and Slavery in the Middle East.

Apart from the evident horrors of kidnapping and forced labor, he states that the death provoking Islamic deportations can by no means be called more humane than those run by Europeans or Americans. He went on to say that Islamic slave work is often incorrectly painted as exclusively domestic. Though the majority of slaves were domestic, there were plenty of slaves who ended up in heavy agricultural work, rarely seen by Western travelers at the time. They mainly encountered and described domestic slavery and hence compared two different types of slave labor, says Lewis.[14]

Additionally, there is a flipside to the fact that most slaves in the Islamic world were used for domestic work: the nature of domestic labor pertains to the reality that most Islamic slaves were women and children, and often eunuchs. Apart from their work as menials, Lewis continues, women were also used as concubines. Muslim owners were entitled by law to the sexual enjoyment of their slave women.[15]

Lastly, defenders of true Islamic slavery may be asked why Sharia has always prescribed that only non-Muslims may be taken as slaves, if the calling of a slave in the Islamic world was such a pleasant one.

The Numbers

Murray Gordon, in his book on Arab slavery, states that an estimated 11 million Africans were exported on behalf of the Islamic trade between the seventh and nineteenth century, exclusive of the number of deaths.[16] Historian Ralph Austen places the number at more than 7 million, up to the year 1600 alone, without taking some of the worst centuries into account. Paul Lovejoy, an expert in African history, calls this number a rough approximation and says that somewhere between 3.5 and 10 million would be accurate.[17]

As with any slave trade, the total amount of deaths during the Islamic trade is likely to have been much higher than the actual number of exported slaves. Crossing the Sahara, for instance, was brutal. In addition, many young male slaves were castrated because of the large demand for these costly eunuchs in the Muslim world. The number of deaths due to these “operations” – which were usually outsourced to merchants from Christian lands and elsewhere, because Islam forbids the practice – were high.[18]

According to historians the total number of African slaves is harder to determine for the Middle East trade than for the Trans-Atlantic export, which Philip Curtin also estimated at around 11 million slaves (between 9.5 and 12 million).[19] The people behind project Voyages see the western number around 12.5 million.[20]

Thoughts on proportions

Despite the similar numbers for both trades, it should be understood that the Western tragedy unfolded in a much shorter time than the Islamic, which is testimony to its grotesque yearly size. On the other hand, one could argue that since populations were much smaller in pre-colonial times, this changes the proportions and therefore the impact on societies, says Harvard scholar Steven Pinker, who studied the number of deaths during each of the largest human atrocities. According to his, sometimes disputed, methodology the “Middle Eastern slave trade” from the seventh to the nineteenth century jumps to number three on the all-time list.[21]

On a side note, the comparison between both systems is not meant to suggest one was worse than the other. The differences in publicity, remorse and the admission of guilt have formed the motivation for illuminating the Islamic trade, as it seems long overdue.

The numbers mentioned above only concern the African continent. Islamic slavery as a whole was, again similar to European slavery, much larger if we look beyond Africa and take into account the Ottoman and Barbary slavery on European and West-Asian territory, or the Islamic states that conquered large parts of India and practiced slavery there for centuries. Many Christians, for instance, have been enslaved by different Islamic states. Historian Robert C. Davis estimates this number at a minimum of 1 million slaves between 1530 and 1780 alone, during the Barbary slave trade.[22]

Abolition

The first Islamic countries began to move towards abolition around 1850. For some Arab countries this process didn’t finish until the second half of the twentieth century, ironically around the time of Muhammad Ali’s conversion. Abolition was mainly prompted by pressure from a number of West-European countries which, not too long before, had begun to abolish slavery of their own accord.[23] Unfortunately, an Islamic variant of the Christian abolition movement was virtually non-existent.[24] This is why, according to many scholars, diplomatic pressure from Europe was crucial.[25]

Bernard Lewis shared this opinion. In his influential work, he wrote that abolition was not likely to have come from the Muslim world because slavery is so embedded in Islam’s social system.[26] Historian William Clarence-Smith in his work, Islam and the abolition of slavery, mentions a long list of orientalists and other scholars who seem to agree with Lewis. But then, with a fair amount of stretching and pulling, he counters this by providing a second list, almost equal in size, of colleagues who supposedly disagree. See the following footnote for a brief analysis of what the author calls ‘orientalist contradictions’.[27] It seems evident that no historian would suggest that there wasn’t a single Islamic voice against slavery. Rather, most conclude that abolition primarily had to come from the West with its fast-growing and goal-oriented abolition movements and their ability to reach beyond the borders of their own empires.

Christian theory and practice

Despite the Christian roots of the abolition movements in the West, it is regularly asserted that the New Testament nowhere calls for the abolition of slavery. Though this claim on itself can be debated,[28] there may be a quick way to drag the contrast between the two religions into the light of pragmatism: Even if we accept, uncritically, what many Muslims and Christians claim, namely that their respective scriptures were at the very least meant to steer followers towards a gradual abolition of slavery, it remains undeniable that, historically, the Christians are the ones to eventually fulfill that promise of their own accord, basing it on their scriptures.[29]

It is of course true that Christians with commercial interests were responsible for one of the worst slave trades known to man. But at the same time other Christians, with a clear religious interest, were responsible for its widespread abolition, at home and abroad.

Temporary revival of slavery

It is no surprise then that it was again Islam that tempted the minds of nineteenth century Africa to commence with a revival of slavery. This was due to the establishment of several new Jihad states. There was the Sokoto caliphate in 1804, the caliphate of Hamdullahi (Masina) in the twenties, Segu Tukulor under al-Hajj ‘Umar in the forties through the sixties, the Samorian state in the seventies and eighties, the Mahdi’s state in the eighties and Rabeh’s state in the nineties.

This string of jihads lashed out from east to west around the Central Sudan.[30] In some towns this led to estimated slave populations of 53 percent, as seems to have been the case in the Segu district around 1894.[31] Around 1820 Egypt was still busy conquering many slaves, now under the guidance of a man ironically named Muhammad Ali. His message to an army unit, as it was about to raid the Nilotic Sudanese people, suggests that there was at times a racial element to the Arab slave trade: “You are aware that the end of all our effort and this expense is to procure negroes. Please show zeal in carrying out our wishes in this capital matter.”[32]

When Egypt began to distance itself from slavery due to British pressure, this led to the aforementioned Mahdi state. Its dynamic leader Muhammad Ahmad, who crowned himself as the Islamic redeemer, resisted Egypt and established a slave trading nation which would dominate the Nilotic Sudan until 1896.[33]

The last slavery states

Slavery remained present in a number of Arab countries until far into the twentieth century. Saudi Arabia and Yemen came to their official abolition in 1962, Oman in 1970. Mauritania followed in 1980 but didn’t criminalize slavery until 2007, resulting in the presence of old fashioned slavery of sub-Saharan black people to this day.[34]

With these facts we come to the second main leg of irony concerning Muhammad Ali’s choices in those years. When the young boxer took an Islamic name, while criticizing America’s slave trading history of 100 years prior, slaves were sold not far from the holy places of Islam in Saudi Arabia.[35]

Malcolm X

This irony may have been even greater for Malcolm X who had already converted to Sunnism. He actually visited Mecca in 1964. One can only speculate on how Malcolm X harmonized the fact that the Saudis had only begun to release African slaves two years prior to his meeting with their king, and his continuous reference to American slavery.

And this slavery did not stand on its own in Saudi history. The practice can be traced back some thirteen centuries, through an uninterrupted line, to the life of Muhammad in the very same areas. These facts did not stop Malcolm X from writing his famous lines in which he praises the Islamic equality he found there. He describes how the Arabs met him with a warm welcome, something he wasn’t accustomed to in America. That this difference between both countries made Malcolm X feel good is no surprise. But was this because of a tolerance towards his particular skin color or his religion? After all he was now a Muslim in an Islamic country. But not everyone was welcomed by the country in this manner. Slavery here had not been based on racism but on religious intolerance. It seems that Malcolm X either could not see this nuance or did not care.

Continued risk

Recent events show that a new revival of slavery is always around the bend. It is no modern phenomenon that the establishment of a caliphate, anywhere in the world, will have disastrous consequences for the fight against slavery. And the fight isn’t over. To this day African slaves can be found in Muslim countries like Mauritania[36], Sudan[37] and Yemen.[38] These modern crimes are echoes of past Islamic states in these regions. In Libya slavery is back after a short period of absence, which seems to be the result of the recent deposition of Khadaffi and the failed attempts to safely rebuild and control the country as well as the subsequent presence of ISIS and other jihadist groups.[39]

Modern condemnation behind smokescreens

Though stories of Islamic scholars who condemn slavery are popular, they always seem at odds with Islam’s history and sometimes even with previous statements by the same source. With some regularity one stumbles upon general condemnations of ISIS by Al-Azhar, while the true position of this leading Egyptian University is often not what people would expect. As recently as 2014 Suad Saleh, professor at Al-Azhar condoned the enslavement of women under Islamic rules.[40] Perhaps a parallel can be drawn between claims of Islamic innocence in our time and the observation made by senior diplomat Sir Arthur Hardinge, way back in 1928, that liberal “Europeanized” Muslims are sometimes inclined to pretending that slavery is not a foundational principle of Islam in order to obtain European favor.[41]

Academic silence

Academically it has been far too quiet with regards to the Arabic slave trade. This goes for the West, which has mostly been preoccupied with its own problematic history, but is also true for the Arabic world, which is disappointing to say the least. The theme of the Arab or Islamic slave trade was and is hardly mentioned, says Murray Gordon. Also, the Western level of shame attached to the practice is still absent in Arab thought. Gordon clarifies that speaking shame of slavery would mean doing so of Islam, which is still unthinkable in most Muslim countries.[42]

Bernard Lewis was another scholar who addressed this academic problem. He observed that the number of studies on the Trans-Atlantic, Roman and Greek slaveries run in the thousands, while a list of works on slavery in the Islamic areas would fit on a single page. Despite this academic silence, the subject is important for virtually every area and time in the central Islamic areas. According to him, there are plenty of sources to work with, but the sensitivity surrounding the matter may be too much for Islamic scholars to see past.[43]

Muhammad Ali’s Islamic ancestors?

As mentioned, it is unlikely for the original ancestors of Muhammad Ali to have been Muslims. However, there is a small chance that this was true for his more recent ancestors from Africa. The portion of Muslims in the slave population on the American continent is estimated to have been no larger than 30 percent, with the understanding that the majority of them were taken to South America.[44] For North America the percentage is sometimes estimated to have been around 10 percent.[45]

What should not be forgotten is the fact that Muslim slaves could have been slave masters themselves, before they were kidnapped and transported to the Americas. After all, there was a widespread presence of slaves in common Muslim households and, as we’ve seen from Bernard Lewis, plantations were not as uncommon as was once believed.[46] For a historical example, one could refer to the life of Muhammad Kaba Saghanughu. A black Muslim who was kidnapped out of Africa and brought to North America as a slave. It is known that his father had an African plantation with about 140 slaves.[47]

Regardless of whether Ali’s more recent ancestors were Muslims, the origins of his people are equally unrelated to Arab and European culture. Additionally, they did not have Arabic but African names. This adds more to the irony of Muhammad Ali’s name change. He took a name which not only bears all connection to his original ancestors but ironically points towards a religious community that has submerged a large portion of their continent in over a millennium of slavery.

II

Muhammad & Ali: Slave Owners

The next leg of irony in the story of Muhammad’s name change may have entered the reader’s mind by now, as we continue to examine whether this choice makes sense for someone who is so specifically anti-slavery and wishes to get rid of his slave name.

Muhammad refers to the founder and prophet of Islam and Ali was the name of his nephew and fourth successor. Both men were factually slave owners according to the most trusted theological sources of Sunni Islam. Not only did they buy and sell slaves, they also took them as spoils of war after the submission of non-Islamic people. Ibn Al-Qayyim, in his famous work Zaad al Ma’aad, mentions 9 female and 28 male slaves owned by Muhammad, one of them being a eunuch.[48] Daniel Pipes estimates the total number of slaves owned by Muhammad as high as seventy.[49]

Muhammad’s African slaves

Some of Muhammad’s slaves were “black”, as the sources call them. One of them is mentioned in a narration by Umar, Muhammad’s second successor.[50] At one point the prophet of Islam bought a slave by trading him for two black slaves.[51] He also owned a black slave called Anjasha, who rode the camels.[52] The Islamic sources speak of another black slave who was shot dead by an enemy’s arrow.[53] A different narration, which does not mention race, tells the story of Muhammad selling a slave in order to help the Muslim master who was in need of money.[54]

Female Slaves

Muhammad also had female slaves, some of which he used for sexual intercourse. This becomes clear from narrations such as one in which Muhammad was able to appease his jealous wives, after they learned of his sexual relations with a slave girl. He did so by promptly receiving a new verse of the Quran from Allah. In the verse, Allah urges him to continue to enjoy that which has been made permissible for him.[55]

Sexual conduct concerning female slaves

Both the Quran and the Hadith literature have always been interpreted to condone unlimited sexual relations with one’s personal collection of female slaves even if they were just captured. This is shown in several narrations which describe scenes after military conquests by Muhammad and his companions.[56] Also, an existing marriage bond between a newly obtained slave and her pagan husband brought no limitations to the rights of Muslims. Such a marriage was simply not acknowledged. Because even when Muhammad’s followers became reluctant to have intercourse with such women, because their imprisoned spouses were nearby, Muhammad had another immediate revelation from Allah, saying it is allowed to have intercourse with wedded slave women.[57]

Muhammad’s nephew Ali had a lot of slave dealings himself. According to one narration he was sent by his uncle and prophet to beat a slave woman who was accused of adultery. He changed his mind when he saw that she was still bleeding from giving birth. However, the narration proves that in general he was not against the idea of owning female slaves.[58] In another narration, in which Muhammad gave him two slaves, Ali did what slave traders do: he sold one of them.[59] And finally there is a narration describing how Ali had intercourse with a slave girl, with the outright permission of Muhammad.[60]

Manumitting slaves

Muhammad also released slaves, sometimes by buying them. This was seen as a pious act in the centuries after. This is regularly mentioned as proof for Islam’s supposed anti-slavery position. However, in practice, those slaves who were eligible for being manumitted were often converts to Islam.[61] Most importantly, the tradition of manumitting slaves was never understood to mean that (even gradual) abolition should be its result. New slaves could always be acquired under the existing Islamic rules. The command in the Quran to free slaves if you see good in them (Surah An-Nur, verse 33) clearly did not compel Muhammad to free his slaves, since he kept many. Additionally, according to a wide group of scholars, the context of this verse alludes to the rule that a slave may buy his freedom, if he has the funds and if the owner considers the slave fit for freedom and in no way harmful to Muslims or Islam.[62]

Bilal ibn Rabbah

Another example of problematic references to Islamic history is the story of Bilal ibn Rabbah, one of the first black slaves to have been freed by a companion of Muhammad. In reality, there is a crucial nuance Muslims should uncover before sharing these events with potential converts. According to the oldest surviving biography on the life of Muhammad, Bilal was traded for another black slave. After all, he had become Muslim during his stay with a pagan master who beat him because of it. Abu Bakr, one of Muhammad’s most trusted companions, saw this and decided to give the slave master a pagan black slave in return for Bilal. This, again, shows that full abolishment of all slavery was never the intention of the founding generation of Muslims.[63] Though Muslim writers do quote this source, they tend to simply leave out the part where the trade is made, perhaps to sustain the common myth that he was bought free because Islam came to abolish slavery.[64]

After Muhammad’s death his companions continued to practice slavery. This is evidenced by the Islamic sources, which mention the buying[65] and selling[66] of slaves as a reoccurring side issue in various narrations. The famous hadith collection Malik’s Muwatta holds a number of narrations which discuss the details of the sale and return of slaves to a great extent. These narrations explain things like what to do when a “defect” is found by the buyer. They even discuss who is responsible if the buyer has “already had intercourse” with a female slave.[67]

It can be no surprise that Islamic states and slavery almost always go hand in hand, even in modern times. The choice of human rights activist Muhammad Ali, to take these two names, is as tragic as it is ironic. Especially since one of the names belonged to the founder of his chosen religion. The general public’s ignorance with regard to these topics is great, which is unfortunate enough, knowing that this has not hindered the spread of misinformation. But the efforts of certain spokespeople to willingly present potential converts with a picture standing so opposite to reality, is more than disappointing.

III

Cassius Marcellus Clay: a white abolitionist

The full name that Muhammad Ali renounced happened to belong to a special Kentuckian. During an interview early in his boxing career Clay explained how he had been named after a local hero, but that he didn’t know what made him so famous.[68]

This brings the tragic irony of Ali’s name change to its fulfilling third leg. For it was this name that belonged to one of the fiercest abolitionists in the history of the United States. A man of stark contrast to the founding fathers of Islam. Cassius Marcellus Clay inherited a plantation from his father. He released its slaves and offered them a payed job. He was a rare pioneer in the Confederate states, having created its only anti-slavery newspaper called The True American.

During his political career Clay survived several attacks on his life by proponents of slavery. Despite this, he never backed away from his stance on the matter. In fact, he began to work for Abraham Lincoln and was one of his advisors for the text of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, written one hundred years prior to the abolition of slavery in Saudi Arabia.[69]

At this point the reader will perhaps understand why the word irony was used so systematically in this article. It is no laughable irony which is described here, but a sad one. Muhammad Ali not only took the name of two medieval slave traders, after converting to the religion responsible for millions of African slaves, but also renounced the name his parents gave him to remember a man who was prepared to die for the freedom of their people.

Islamic “evangelization” is often custom made

Despite these facts of history many people still convert to Islam specifically because of an alleged anti-slavery status. This is probably a result of the academic silence surrounding the Arab/Islamic slave trade and a lack of interest in media, documentary- and moviemakers. Another factor is undoubtedly found in the many attempts by Muslim leaders to increase the popularity of Islam by using fantastical stories like the one about Bilal ibn Rabbah. This form of deception is often applied to people with African roots as well as other groups.

To some it is known that Islamic dawah is often customized: the feminist is told that Muhammad was a champion of women’s rights; those with an affinity for science will hear that the Quran holds numerous scientific facts which were not known to mankind until many years after Islam’s inception; and the searching soul with an African heritage is given half-truths and plain lies, either without conscience or without knowledge, about how Islam abolished slavery. In the latter case, both history and the continued descriptions of Sharia are ignored. When people are not only looking for religious truth but also for their cultural roots, as seemed to be true for Muhammad Ali, their heart’s desires are in danger of being used by Islam activists, only to point them in the wrong direction all over again.

The tragedy behind Ali’s choice is great and it is to be hoped that those who have the opportunity to change their minds will have attention for the stated facts. But above all stands the necessity for Christians to take away people’s reasons for doubting the good truth of the Christian message and looking elsewhere, lest the beautiful lie retain its attraction.

It seems only appropriate to close with some words by William Wilberforce, a pioneer of the British abolition movement:

“If to be feelingly alive to the sufferings of my fellow-creatures

and to be warmed with the desire of relieving their distresses, is to be a fanatic,

I am one of the most incurable fanatics ever permitted to be at large.” [70]

Footnotes

[1]

Mahdi refers to the Islamic “redeemer” whose arrival is said to precede the end of times. Wallace Fard Muhammad is still identified as this Mahdi today on the official website of The Nation of Islam: https://www.noi.org/noi-history/

[2] YouTube; March 6, 1964: Cassius Clay becomes Muhammad Ali. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tsL4r_yhMLM

[3] Lovejoy, Paul, E.; ‘Transformations in Slavery, a History of Slavery in Africa’, third edition (2012), Cambridge University Press, p. 15; see also: Brunschvig, R.; ‘Encyclopaedia of Islam’; E.J. Brill (1986); Second Edition, Volume I, p. 31

[4] Lovejoy, p. 15

[5] Ibid., p. 24

[6] Gordon, Murray; ‘Slavery in the Arab World’; New Amsterdam Books (1989), p. 19

[7] The most involuntary form of slavery, whereby one is kidnapped and then forced into servitude, is unequivocally condemned in 1 Timothy 1:10. Then, 1 Corinthians 7:21-24 says that bondservants should obtain their freedom if they can, which demonstrates a clear preference. Though Paul speaks to Christian bondservants here, there is nothing to suggest that this shouldn’t refer to people of other faiths. The Greek word here is δοῦλος (translit.: doulos), which can refer to slaves and voluntary bondservants. Also, Ephesians 6:9 is a clear testimony to the thought that slave and master are both equal before God, or as the original text says: “God is not partial”. Paul then urges, again to both slave and master, to “do good” to each other regardless of their respective roles. This shows that the first Christians attempted to change hearts and minds everywhere, rather than try and change the man-made laws of the Roman Empire. Numerous other texts instruct Christians to give to orphans, widows and the poor, which may have resulted in a reduced number of people having to lower themselves to the status of a bondservant. See: Matthew 6:2-3; 19:21; 26:11; Luke 14:13; Romans 15:26; Galatians 2:10.

[8] Gordon, p. 44

[9] Clarence-Smith, W.G.; ‘Islam and the Abolition of Slavery’; Hurst & Co. (2006), p. 16-17

[10] Lovejoy; p. 3, 16, 30; see also: Lewis, Bernard; ‘Race and Slavery in the Middle East’, Oxford University Press (1990), p. 53

[11] Lovejoy, p. 31; Willis, John Ralph: ’Slaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa (vol. II): The servile estate’; Frank Cass & Co. (1985), p. 21

[12] Lovejoy, p. 63

[13] Ibid., p. 30

[14] Lewis, p. 100-102, 14

[15] Ibid., p. 14

[16] Gordon, p. ix

[17] Lovejoy, p. 25 & 27

[18] Ibid., p. 35

[19] Curtin, Philip, D.; ‘The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census’; The University of Wisconsin Press (1969), p. 87

[20] Voyages: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. URL: http://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates

[21] Pinker, Steven; ‘The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined’, (Viking, 2011), p. 195 (see p. 193-194 for his methodology).

[22] Davis, Robert C.; ‘Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: white slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500-1800’; Palgrave Macmillan (2003), p. 23

[23] Lovejoy; p. 136, 148, 150; also see: Gordon, p. 161

[24] Gordon, p. 21, 44

[25] Gordon, p. 152-153; Brunschvig, p. 36; see also: Lovejoy, p. 216

[26] Lewis, p. 78-79

[27] On p. 16-19 of his book Clarence-Smith first refers to 16 orientalists who quite straightforwardly conclude that slavery had always been an integrated part of Islam, making abolition a tough sell in Islamic lands. Counter to that the author refers to 12 orientalists who supposedly have challenged these assumptions. His personal preference evidently goes to the latter group. Perhaps this is the reason for the sometimes far sought nature of his examples. For instance, he mainly mentions the opinion of the scholars concerning the Islamic scriptures with only a few mentions of minority voices who began to speak out against slavery (mainly at the beginning of the nineteenth century). One scholar, Murray Gordon, whose work is referenced in this article, nowhere says what Clarence-Smith indirectly makes him say on page 19, placing him in the second list. Even on pages mentioned by Clarence-Smith for this purpose, Gordon in reality says that the main motivation for Islamic abolition was European pressure, perhaps combined with expected economic and political benefits foreseen in the international future if abolition was pursued. On page x of his mentioned work, Gordon straightforwardly says that abolition by Islamic states was not a moral choice since slavery is sanctioned by the Quran. Surely a statement so similar to those of Bernard Lewis and others should have secured his place in the first list, but for some reason he ended up in the second. On page 209, also mentioned by Clarence-Smith, Gordon says that most Islamic leaders lacked the will to agree to abolition and, on page 208, that the European colonization of Africa vastly accelerated the process of abolition. On page 21 and 44 Gordon says that the well-known anti-slavery movements of the West were virtually non-existent in the Islamic world. On page 19 he states “…there is nothing in the Prophet’s prescription regarding slavery that would have us conclude that he even as much favored a gradual abolition of slavery.” And finally, Bernard Lewis, who Clarence-Smith accuses of “sweeping generalizations” in his description of the Islamic stance, in reality does leave room for initiatives by Muslim leaders. This is shown by his statement that “…for some time progress in this matter was due almost entirely to European urging and action…”, (Lewis, p. 79).

[28] See endnote 7

[29] See for instance the book Real Christanity by William Wilberforce, the great evangelical pioneer of the British abolition movement

[30] Lovejoy; p. 155

[31] Ibid., p. 191

[32] Ibid., p. 148

[33] Ibid., p. 149

[34] Klein, Martin A.; ‘Historical Dictionary of Slavery and Abolition’; Second Edition (2014), p. xxiv-xxv

[35] Gordon, p. 233-234; Chande, Abdin; ‘Encyclopedia of anti-slavery and abolition’, Volume 2 J-Z; Greenwood Press (2007), p. 599

[36] The Guardian, ‘The Unspeakable Truth about slavery in Mauritania’. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/jun/08/the-unspeakable-truth-about-slavery-in-mauritania

[37] University of Central Florida; ‘A Modern Slave’s Story: Francis Bok; URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T_KZyjUVkMc

[38] Al-Jazeera; ‘The Ongoing Fight To Free Thousands Of African Slaves In Yemen’; URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KVuQTiQNJOE

[39] CNN; ‘People for sale, Where lives are auctioned for $400’; URL: https://edition.cnn.com/2017/11/14/africa/libya-migrant-auctions/index.html

[40] Memri TV, Al-Azhar professor Suad Saleh: In a legitimate war, Muslims can capture slavegirls and have sex with them. URL: https://www.memri.org/tv/al-azhar-professor-suad-saleh-legitimate-war-muslims-can-capture-slavegirls-and-have-sex-them

[41] Clarence-Smith, W.G.; ‘Islam and the Abolition of Slavery’; Hurst & Co. (2006), p. 128

[42] Gordon, p. x

[43] Lewis, preface

[44] Jaques, R. Kevin, Meigs-Jaques, Donna L. in: ‘Encyclopedia of Religion in the South’; Mercer University Press, Second edition, p. 394

[45] Tweed, Thomas, A.; ‘Islam in America: From African Slaves to Malcolm X’, University of North Carolina. URL: http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/twenty/tkeyinfo/islam.htm

[46] Lovejoy, p. 216

[47] Madden, R.R.; ‘Twelve years in the West Indies’ II, p. 35; in: Addoun, Yacine Daddi and Lovejoy, Paul; ‘The Arabic Manuscript of Muhammad Kaba Saghanughu of Jamaica, c. 1820’, p. 11; see also: Lovejoy, Paul; ‘Transformations in Slavery’, p. 114

[48] Islamqa.com; Fatwa 26067. URL: https://islamqa.info/en/26067

[49] Pipes, Daniel; ‘Slave Soldiers and Islam; the Genesis of a Military System’; Yale University Press (1981), p. 140

[50] Sahih Bukhari, book 91, hadith 368. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/91/368

[51] Sahih Muslim, book 10, hadith 3901. URL: https://muflihun.com/muslim/10/3901

[52] Sahih Bukhari, book 73, hadith 182. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/73/182

[53] Sunan an-Nasa’i, book 35, hadith 3858. URL: https://muflihun.com/nasai/35/3858

[54] Sahih Bukhari, book 34, hadith 351. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/34/351 ; see also: Sahih Bukhari, book 79, hadith 707. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/79/707

[55] The Koran, chapter At-Tahriem (66), verse 1; Sunan an-Nasa’I, book 36, hadith 3411: URL: https://muflihun.com/nasai/36/3411

[56] Sahih al-Bukhari book 8, hadith 367. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/8/367; Sahih Bukhari, book 62, hadith 137. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/62/137; Sunan Abu Dawud, book 12, hadith 2167. URL: https://muflihun.com/abudawood/12/2167; Sahih Muslim, book 8, hadith 3373. URL: https://muflihun.com/muslim/8/3373; Sahih Muslim, book 8, hadith 3371. URL: https://muflihun.com/muslim/8/3371

[57] The Koran, chapter An-Nisa (4), verse 24; Sahih Muslim, book 8, hadith 3432. URL: https://muflihun.com/muslim/8/3432; Sunan Abu Dawud, book 12, hadith 2150. URL: https://muflihun.com/abudawood/12/2150

[58] Sahih Muslim, book 17, hadith 4224. URL: https://muflihun.com/muslim/17/4224; Jami’ at-Tirmidhi, book 15, hadith 1441. URL: https://muflihun.com/tirmidhi/15/1441

[59] Sunan Ibn Majah, book 12, hadith 2249. URL: https://muflihun.com/ibnmajah/12/2249; This hadith is deemed Daif, which means weak. However this does not imply that the events described did not happen, as some may incorrectly assert. The probability is still substantially high, only less than narrations in the authentic (Sahih) category. For an Islamic scholar’s explanation see Youtube: ‘The hadith is weak (daief) brother! Sheikh Hamza Yusuf’; URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COrxzfd5d2k; The reason why Muhammad seemed to frown upon Ali selling one of the slaves must be viewed in light of Islam’s restriction on splitting up related slaves.

[60] Sahih Bukhari, book 59, hadith 637. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/59/637

[61] Clarence-Smith, p. 22

[62] See the tafsir (exegeses) of Ibn Kathir, the two Jalalayn’s and in Tanwîr al-Miqbâs min Tafsîr Ibn ‘Abbâs as well as in Tafhim al-Qur’an by Maududi.

[63] Guillaume, A; The Life of Muhammad, a Translation of Ishaq’s ‘Sirat Rasol Allah’, Oxford University Press (1998), p. 143-144

[64] https://discover-the-truth.com/2018/03/26/bilal-ibn-rabah-tortured-by-the-polytheists-of-quraysh/

[65] Sunan Abu Dawud, book 12, hadith 2155. URL: https://muflihun.com/abudawood/12/2155; Sunan Abu Dawud, book 24, hadith 3426. URL: https://muflihun.com/abudawood/24/3426 ; Sahih Bukhari, book 34, hadith 440. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/34/440 ; Malik’s Muwatta, book 17, hadith 20. URL: https://muflihun.com/malik/17/20

[66] Sahih Bukhari, book 34, hadith 362. URL: https://muflihun.com/bukhari/34/362

[67] Malik’s Muwatta, book 31, hadith 4. URL: https://muflihun.com/malik/31/4

[68] Youtube: ‘Muhammad Ali interview on his name’; URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HxFHQd-rj0A

[69] Klein, p. 116

[70] Wilberforce, Robert Isaac and Samuel; The Life of William Wilberforce (1938), p. 290